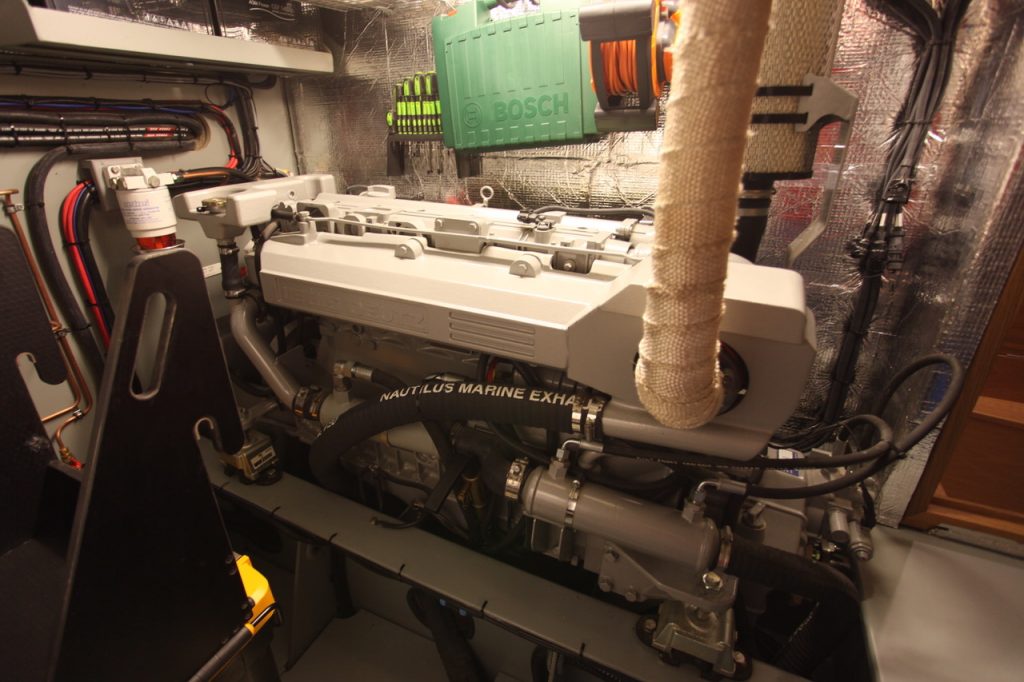

Aleau’s engine is a 6-cylinder turbo-charged 175 HP Vetus-Deutz diesel. It is “keel cooled.” Most barges (and every ship that goes to sea) use water from the canal (or ocean) for cooling. You can see the used water squirting out at the stern. On a canal, this type of cooling system can become plugged with weeds. Aleau has a closed circuit of coolant pipes – like a radiator in a car. The pipes sit in the canal water but are protected from damage. It is a real bonus not to have to worry about weeds clogging the cooling system.

The vertical tank is the hot water tank. (Water in it is heated by three methods. When underway, hot water from the engine runs through tubes in the hot water tank. When plugged into shore power, an immersion heater can heat the water – as with a home hot-water tank. When needed, our diesel boiler will automatically send hot water to the tank.) To the right is the generator. In between the two is part of the air-conditioning system. (There are separate thermostats in each cabin, in the living room, and in the wheelhouse.) Hidden behind the hot water tank is a diesel boiler. It supplies hot water to both the hot water tank and to the radiators. Also out of view are the pumps (about 10 of them) – for domestic (potable) water, for the grey-water tank (waste from sinks and showers), for the black-water tank (waste from toilets), and for the air-conditioning system.

The engine has two alternators. One is used to charge the engine-start batteries. Just as with a car – except Aleau has two 12-volt batteries. That big diesel needs lots of amps to get it going. The batteries are wired in parallel so they still produce 12-volts – not the 24-volts they would produce if wired in series. It’s the high number of amps that are needed to turn over the engine – not the voltage.

The other alternator mounted on the engine is even bigger than the one charging the engine-start batteries. It charges the domestic batteries.

The domestic batteries are 12 two-volt batteries wired together to provide 24-volts. They’re big – each one weighs about 80-pounds. They power absolutely everything on Aleau. Two inverters change 24-volts DC to 240-volts AC.

As mentioned, the domestic batteries supply electricity for everything on Aleau. When cruising, the domestic alternator on the engine keeps the batteries charged. When moored, and if we’re lucky, we may (for a price) be able to plug into 240-volt shore power. If we’re tied up along a canal bank, we can turn on the generator. It’s noisy and we try not to use it whenever possible. If we’re not plugged into shore power and we’re not using the generator, every bit of electricity we use will come from the domestic batteries. We never let get them get below 80 per cent. With the bare minimum running (fridge, freezer, a few lights), we will drop to 80 per cent overnight. Come morning, we either fire up the engine and start cruising or we run the generator for an hour. Some of our appliances that require a lot of electricity will not turn on unless we are connected to shore power or running the generator – a safety feature to keep us from draining the batteries.

The batteries used to start the engine and the generator are totally separate from the domestic system. If we should happen to drain the domestic batteries, at least we’ll be able to start the engine or generator and produce electricity to replenish them – if they haven’t been permanently damaged by having been drained to too low a level.

We often take for granted utilities in a home. We turn on the tap knowing there will be water. We flick on a light switch knowing there will be electricity. We flush the toilet knowing the waste will flow into the municipal sewage system. We never have to worry about using too much electricity or water – or flushing the toilet too often.

It’s different on a barge. We are not connected to anything. We supply everything.

We carry 3,000 litres of potable water. When it’s gone, we have none. Not for drinking, not for cooking, not for washing, not even for flushing the toilet.

Electricity is also finite. We must be frugal about its use. If we use too much, we risk draining our batteries.

Even sewage has to be managed. Toilet waste is pumped into a 1,000-litre black-water tank. When it’s full, the toilets will back up. While the law says all new boats must be built with black-water tanks, there are very few pump-out stations. That means raw sewage must be emptied into the canal or river. Some “live aboards” empty their black-water tanks directly into the marina. This is frowned upon. Most bargees will go for a “black-water cruise” and once away from the marina will empty the tank. They will do so while moving so as to spread the discharge over a wider area. Not ideal – but until more pump-out stations are built, there is no other option.

The grey-water tank holds waste water from the sinks and showers. When the 15-litre tank is full, it automatically empties – wherever you happen to be. This is not environmentally friendly as the waste water often contains soap and detergent. When cruising through environmentally sensitive areas (such as oyster beds), the grey water must be (by law) diverted to the black-water tank.