The chapter title, “Signs, Signs, Everywhere a Sign” is from a hit song from 1971. As Jeannie and I are Canadian, I should point out that “Signs” was written and performed by a Canadian group from Ottawa, The Five Man Electrical Band.

This page is a mini-guide to the signs we see when cruising. Some of them are common sense and you’ll figure them out immediately. Others may be far from clear. They are all the product of CEVNI regulations.

CEVNI stands for “Code Européen des Voies de la Navigation Intérieure.” While the term is in French, they are not French regulations. They fall under the auspices of the United Nations and were created to allow vessels from European nations to travel the inland waterways of Europe and understand the rules of the road (in this case, canals and rivers) regardless of language. I should point out that many of the CEVNI signs and regulations are unique to CEVNI and do not exist anywhere else in the world. The reason is European waterways are the most congested in the world with vessels (some of them huge) routinely passing closer to each other than anywhere else.

To give you an idea how close, the YouTube video below was shot by my friend Lisette onboard Catharina Elisabeth. It was moored in Pont du Loup in Belgium as a ‘commercial’ left its mooring in a shipyard and turned onto the Sambre river. It had less than a metre on each side. Good piloting.

The sign below shows the maximum speed allowed on that stretch of the waterway. In this case, it’s 6 km/h – although since water skiing is allowed for a short distance on this part of the Saône, boats towing water-skiers can go faster. 6 km/h is the maximum speed on all canals (and there can be slower sections where even 6 km/h is deemed too fast). Rivers have higher speed limits but as you can see below, along some stretches even a large river can have a lower speed limit.

The sign above should not be confused with the sign below. Although similar looking, they have nothing to do with each other. Common sense might lead one to assume the sign below means the speed limit is no longer 40 km/h – although I don’t think there’s a speed limit on the water that high anywhere.

No, it means you can’t anchor or moor for 40-metres from the sign. I told you it’s impossible to guess what some of the signs mean. Memorizing the CEVNI book is the only way – at least it’s the only way to pass the exam. When cruising, a laminated page with all the signs is the best way to go.

Another common sign is one that prohibits oncoming boats from passing each other. You can see in the background there is a narrow flood-gate. No way could two boats squeeze in there at the same time. If you see another boat is going to get there before you, you must pull over and wait. You also can’t pass another boat going in the same direction as you. The sign beneath it is obvious, No Parking. Since there must be room for a boat to pull over if another boat is passing through the flood gate, there can be no parking or mooring between the sign and the flood-gate.

In the photo below, a white diagonal on a blue background means the restriction has ended. It usually doesn’t say what the restriction was – but whoever is at the helm should know as, up until the blue sign, he or she had been obeying the restriction (or should have been). It may be the No Passing and No Parking signs above – or it may be a slower than normal speed limit sign. It could be anything – but it is no longer in effect once past the blue sign. It’s redundant, but the bottom sign says parking is, once again, permitted. This is a rarity. Usually, there’s no mention of what is once again permitted.

The first of the two signs below might not be obvious. It means Extra Vigilance Required. It could be for a number of reasons – but in this case, the second sign explains why. It warns the boater to keep an eye out for boats entering the river from a smaller waterway on the right. That smaller waterway is the entrance/exit to our marina in Auxonne – just before the flags.

Here’s one that makes absolutely no sense to me. The two yellow-diamonds on the bridge mean traffic under that arch is one-way in your direction. You will not face any oncoming traffic. But a single yellow-diamond means two-way traffic – be prepared for a boat coming in the opposite direction. So, one yellow-diamond means two-way traffic and two yellow-diamonds mean one-way traffic. Who came up with that? Isn’t it counter-intuitive?

The signs with horizontal red-and-white stripes on the bridge mean Do Not Enter. They are used in many locations – such as where water flows into a dam. In this case, coming in the opposite direction, there will be two yellow-diamond signs on one of the arches that says No Entry from this direction. The boat passing under that arch will know not to expect any oncoming traffic.

On many waterways, you’ll see signs like this.

They indicate the “PK Number” (Point Kilometrage). Unlike traveling anywhere else in the world by boat, latitude and longitude are not used to describe your position. Instead, on the inland waterways of Europe, PK numbers are used. These signs appear every kilometre – and also appear in navigation guides. It makes it easy to know exactly where you are.

The sign below is very important. It warns of dangerous conditions on the river. If the water level reaches “I” – extra caution is required. If it reaches “II” recreational boats such as Aleau are not allowed on the river. (Large commercials are still allowed.) You may remember in Chapter 88 the photo of a boat that had been on its way from the Netherlands to Barcelona that had to take shelter in our marina. The level on the Saône had reached “II” and it had to get off the river. When the water reaches “III” no boats of any kind are allowed on the river.

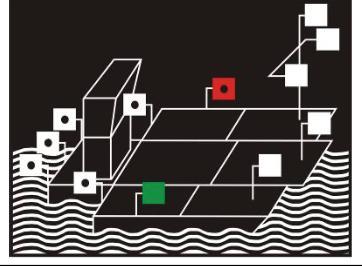

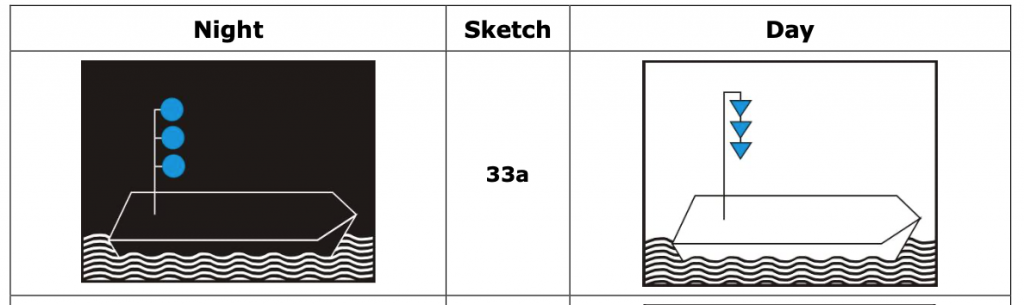

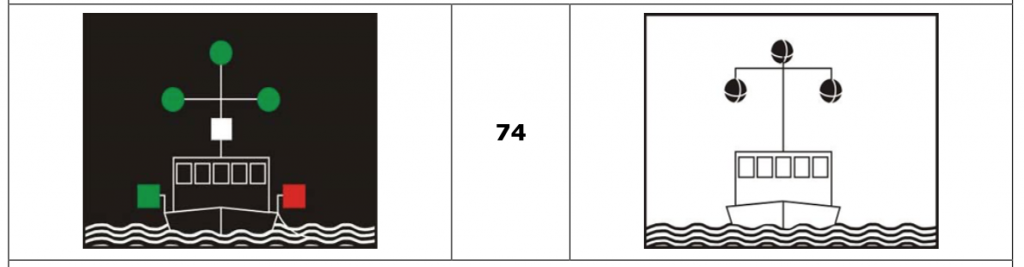

The most complicated section of the CEVNI rules (at least for me) is the section on the markings that are displayed on vessels. Since we’re not cruising at the moment, I can’t get a photo – but here are some sketches taken from the CEVNI book – showing how complicated they can be – and how seriously you should take them. They are some of about 70 different warnings on boats that you may see.

There are a few I hope I never see.

Three vertical blue lights (at night) or three vertical blue cones (by day) mean the vessel is carrying explosives. Stay away. A single blue means it is carrying inflammable material. Stay away. Two blues mean it is carrying material that is dangerous to one’s health. Stay away.

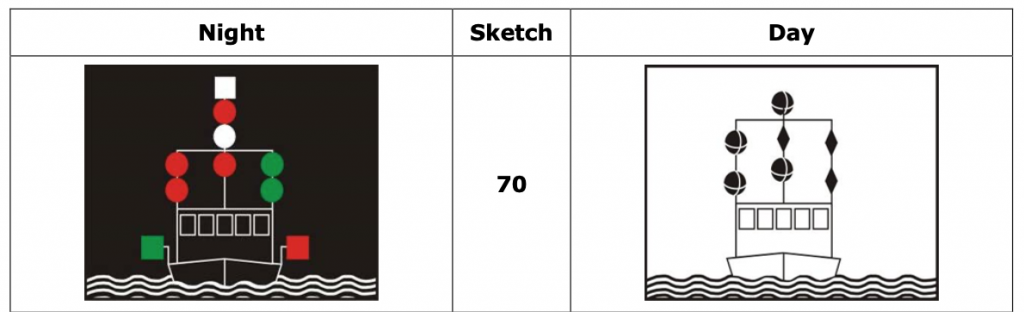

Here’s one I really, really hope I never see.

Three green lights (at night) or three black balls (by day) mean the vessel is carrying out mine-sweeping operations. Get the hell out of there! If you think mine sweeping is a thing of the past, take a look at the video below. There are still unexploded bombs on some European waterways. This video was shot just a few months ago

If you’d like to know more about the CEVNI signs, here’s the official book.

https://wiki.unece.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=25265142

There’s a lot there. Jump ahead to Pages XV and XVI and look at Annex 7 for signs, Annex 8 for buoys and channel markers, Annex 6 for horn signals, and Annex 3 for flags and balls that must be displayed on various type of vessels during the day and lights that must be displayed at night.

Passing an exam on CEVNI is required in order to get a boating license in Europe. If you’ve looked at the annexes in the CEVNI book, you’ll see that a lot of studying is required.

In the UK, to get an ICC through the Royal Yachting Association, the CEVNI test is a piece of cake. You need only know the most common CEVNI signs and you’re not timed. (The UK doesn’t use CEVNI. Is that why the RYA is less diligent in testing potential bargees heading to Europe?)

In France, it is tougher. Way tougher. You are expected to know every single CEVNI sign and every single combination of lights, flags, and balls that can be displayed on a vessel. In addition, the exam is timed. Twenty seconds per question. It’s done electronically. If you haven’t chosen an answer (It’s multiple choice) within that time, you have flunked that question and the electronic box jumps to the next question. You cannot go back. You cannot review your answers at the end. Most people flunk their first attempt at the exam. If you’re thinking of getting an ICC in order to operate a boat in Europe and want an easy test, go to the UK and take the exam there. Or, attend an RYA school in France. (See below.)

The RYA also offers the license required in order to operate a VHF radio. But, as with CEVNI, the rules for using a radio in Europe (Indeed, the radio itself) are totally different from what is taught by the RYA. Learn what they teach you, pass the exam, and then forget everything you memorized.

The best of both worlds… If you need to get an ICC and plan on boating in France, Steve Bridges and his wife, Jo, have the answer. They operate a barging school (in English) in southern France. You’ll learn all you need to know to pass your exam – and do it on the type of waterway on which you’ll be cruising – a narrow canal with many locks. They are affiliated with the RYA – which means the CEVNI test couldn’t have been made any easier. For more information, go to their website – Bargecraft.com

Unfortunately, Steve and Jo do not offer a VHF radio course. For now, you’ll have to go to England, take the RYA VHF course, pass the exam – and then unlearn just about everything they taught you. It would be nice if the RYA realized there are entirely different radio procedures in Europe (not just in France).

If you would like to test your knowledge of the CEVNI signs (and knowledge of French boating terms as well as the use of VHF radios in Europe), below is an excellent site. Once there, click on “Tests Fluvial” at the top. The default setting gives you 30 seconds in which to answer each question. (The exam in France gives you just 20 seconds for each question – and you can’t go back, not even at the end.) Sometimes, there are two correct answers. If you choose only one, you get no points for that question. Good luck.

https://www.loisirs-nautic.fr/test-permis-fluvial-reforme.php?

If you’d like to do it on your phone, there’s an app for that. In the App Store, download “Examen Permis Bateau – Fluvial.” (Not the one titled “Côtier.”). Like the link above, the test is in French. It’s very well done. (And it’s free.)

Not listed in CEVNI – but important to know (and are part of the exam in France) – are the lights used at locks.

At the entrance to a lock is a triangular panel with three lights. If one red is illuminated (as below), the lock is closed and you must stay well back and wait. There may be a boat coming in the opposite direction and you must give it room to exit and get past you. A single red light means the lock is closed – but will become available. Two red lights, one on top of the other on the left side of the panel means the lock is closed – for a long time. It may be for repairs – but whatever the reason, don’t hang around. Make a U-turn (Let’s hope there’s room.) and go back where you came from. If you see red and green lights (across the bottom of the panel), you’re in luck. It means get ready, the doors are about to open. As soon as the red goes out and just the green remains on, you are cleared to enter the lock.

Dave Oare grabbed this shot after the light turned green and Wanderlust made its way into the lock.

How the locks function differs from waterway to waterway. On some rivers and canals, a pole hangs in the middle of the channel. The helm has to manoeuvre his (or her) vessel – very slowly – up to the pole. The crew has to turn the pole so that a signal is sent to the lock letting it know you are there. A yellow light (at the bottom of the panel above) starts to flash to let you know your signal has been received. It’s good to know as the single red light could remain illuminated for quite some time – especially if there is traffic coming the other way. Hang back and wait. Barging is not something you do if you’re in a hurry.

Above is the pole, and yes, it can be just as difficult to see when you’re approaching it on the water. To the right of the pole, a sign telling you which way to turn the pole. (The tighter shot below is of the same lock but coming from the opposite direction.)

Once in the lock, you must position your boat so that you can reach out and push the blue pole in the photo below straight up. I can attest that from the aft deck of Aleau, it is not an easy task. With my arm extended all the way out, I often can’t get the pole to rise. I have to climb over the railing – and holding onto it with one arm, try to raise the pole. Once that’s done, the sluices will open and water will begin to rush in – if going upstream. It’s important that ropes are already around the bollards and the crew at the bow has a firm grip. If not, Aleau could be tossed around the lock like a toy.

If going downstream, the water gently flows out of the lock. There’s still danger. It’s important to make sure ropes don’t get jammed. Jeannie and I both carry a knife so that we can immediately cut the rope if it jams. We had it happen once and it’s not something we want to ever happen again. The red pole is there if there is an emergency. Raise it and everything stops.

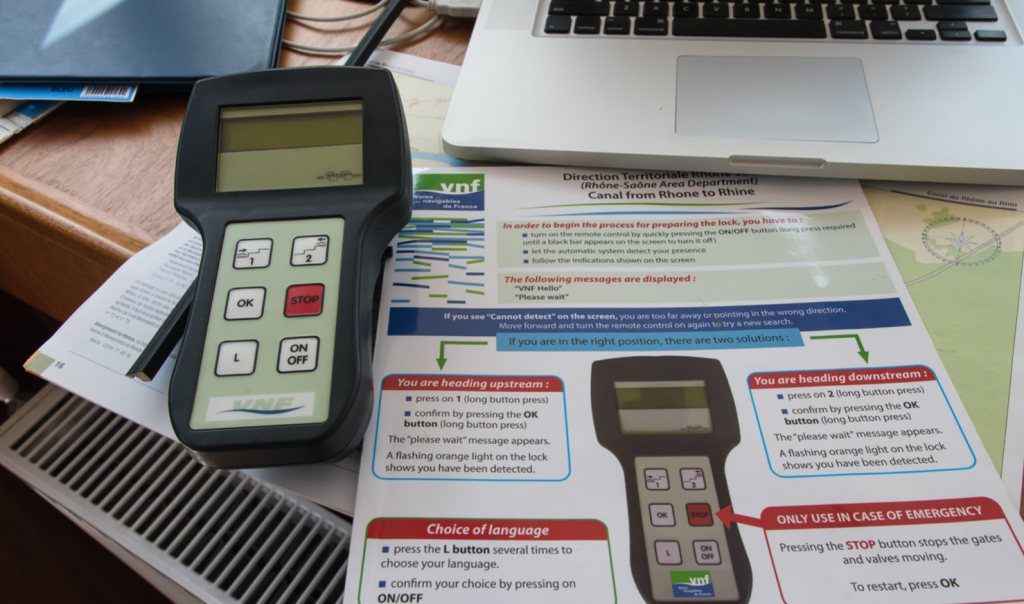

The hanging poles (Three photos above) are only used at locks where there is no lock-keeper. You’re on your own. Thus, the red “Emergency” rod. You’re also on your own on canals that supply a remote control.

Dave Oare on Wanderlust took this photo of the remote he was given when he and Becky cruised the Canal du Rhône au Rhin – the one Jeannie and I plan to take this summer. Covid permitting. I think the remote will be easier than lining up with a dangling pole in a strong crosswind.

As mentioned in Chapter 14, on some canals a VNF worker operates the locks. All you have to do is navigate in and get your ropes around the bollards. The worker travels with you (but faster) on a motor scooter and has each lock ready with the gates open before you arrive.

At the other extreme are canals that not only have no one to help you – but have no motors to operate the gates and the sluices. They are truly manual with the bargee doing all the work. Good exercise.

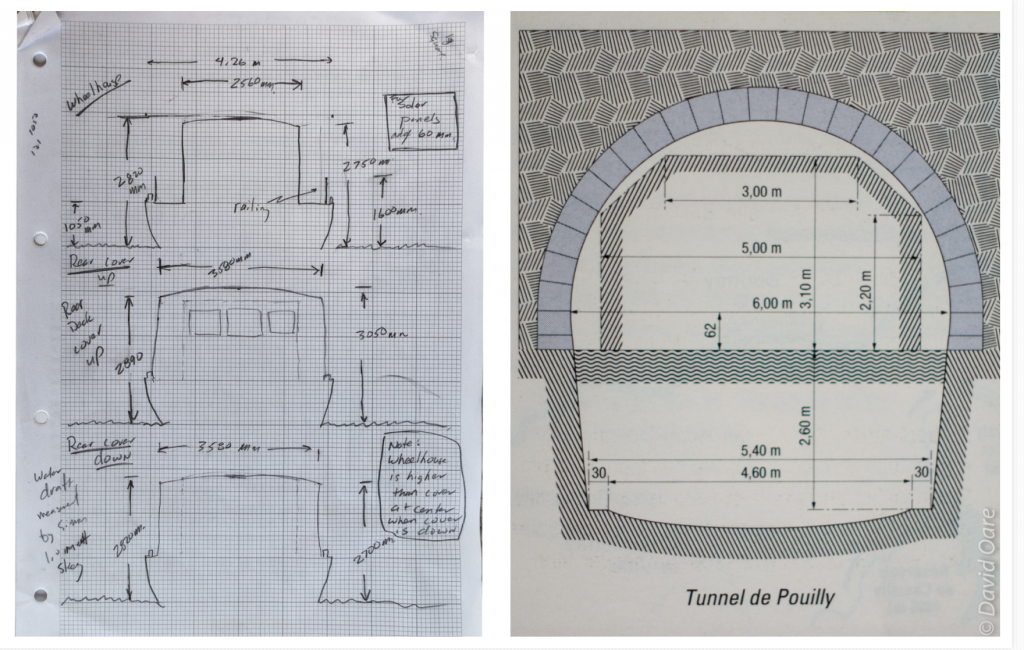

The lock above is on the Canal de Bourgogne. You may recall (Chapter 14) that we did take it to Dijon. But if we want to pass through the lock above, we’d first have to fit under the Pouilly Tunnel.

The photo above is a bit deceiving – the air-draft is not as generous as it first appears.

We’ll have to do some serious measuring before even thinking of going through it. The sketch below shows Dave Oare did his calculations before attempting the Pouilly Tunnel – but Aleau is a lot taller than Wanderlust.

If we get there and find out Aleau is too tall, there’s nowhere to turn around and go back.

We’ll let you know what we decide.