Thrilled with my birthday lunch but anxious to resume our travels, it was time to cast off. Shortly after leaving Compiegne, a fork in the river. We have spent a lot of time on the Oise. This time, we’ll be turning onto the Aisne, something new for us.

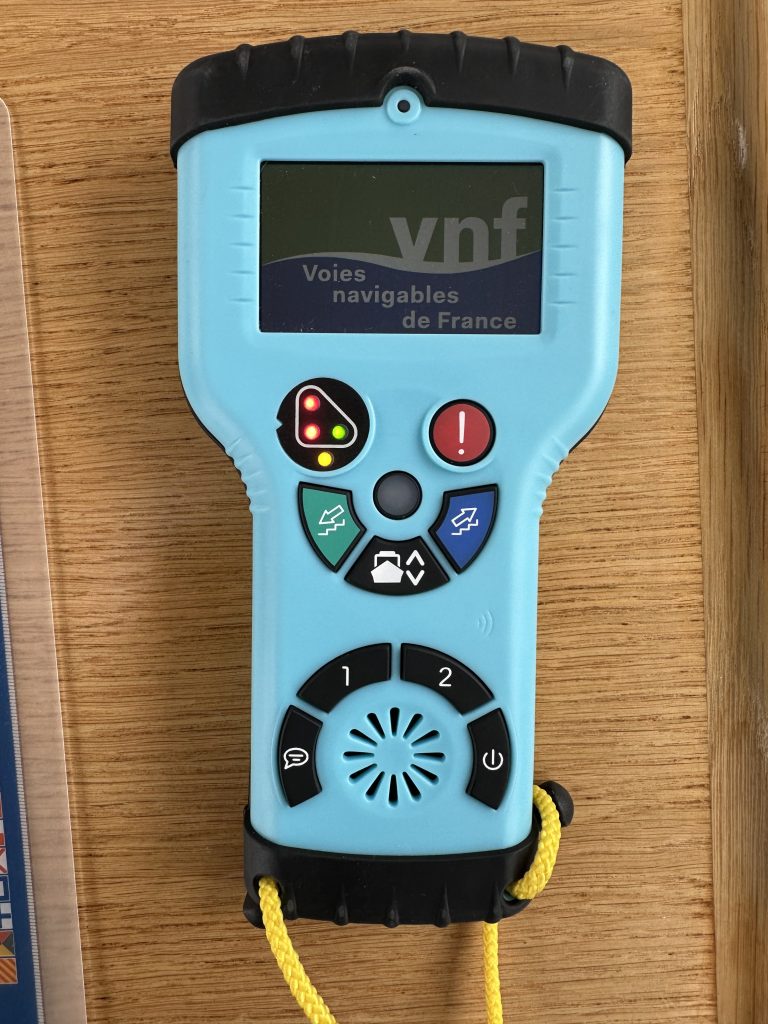

Not new but something we haven’t done in a while and had to remember how to do – operating the locks ourselves. We were given a remote control. The top left display mirrors the lights at the lock. In ‘Test’ mode, they all come on. Two red (not what we ever want to see) means the lock is closed – not operational. Come back tomorrow? Next month? A single red at the bottom means the lock is not ready – but is operational. When both the bottom red and the green are lit, it’s good news – the lock is being prepared for us and the doors will soon open. When they are fully open, just the green light will be showing. Those lights are at every lock. The yellow light is only at locks that we operate. About 100-metres from the lock door, Jeannie pushes either the green or blue button (depending on whether we are going downstream or upstream). If the receiver at the lock gets Jeannie’s signal, the yellow light on the large board at the lock and on the remote will come on. It’s reassuring when we see it – nerve racking when we don’t. (If the yellow doesn’t come on, we have to track down the right VNF person and have him drive to the lock we’re at to fix the problem – while we sit in the middle of the canal – with a current pushing us – and wait.) If there’s a boat already in the lock (traveling ahead of us or coming the other way), the red stays on until it’s out. If the lock is free, the red and green will come on to tell us the lock is either being emptied of filled – depending on if we’re going upstream or down. We wait for just the green and then go in.

I should point out that once we get ahold of the VNF, a truck always arrives within minutes to fix the problem. They are responsible for thousands of kilometres of rivers and canals but always seem to have someone near us. We are very appreciative of the work they do.

There’s still more to do in a “Do It Yourself” lock – and it’s not done by remote control.

Once we’re inside the lock, Jeannie has to raise a blue pole to set everything in motion – closing the gates, filling or emptying the lock, and then opening the gates when the water on either side of the gate is at the same level.

If we’re going downstream, the lock is full as we enter. It’s a simple matter while standing on Aleau to reach over and raise the blue pole. (The red pole is for emergencies.)

If we’re going upstream, the lock is empty when we enter. The blue pole is now not only hard to reach, it is covered with thick slime. It is heavy and can be so slippery that even with gloves, it can be almost impossible to lift. It’s a dirty job but somebody has to do it – almost always Jeannie. She also has to make sure ropes run from Aleau, around the bollard in the lock, and back to Aleau. With Aleau sitting in the bottom of the lock, that bollard can be impossible to see. Getting a rope around it while not being able to see it is even more difficult than impossible.

Compared to others, this blue pole is relatively clean. Because of Aleau’s position in the lock, Jeannie can only reach the bottom of the pole. If it’s too heavy or slippery to lift by grabbing it, she can sometimes get her hand underneath it and push it up. Either way, it means reaching through a very slimy ladder. You don’t wear your best outfit when barging.

I found a shot that better represents how dirty these poles can be.

And one that shows how Jeannie bravely deals with them. At least she didn’t have to thread her arm through a slimy ladder to reach it.

There are locks without remote controls that we still have to operate on our own. A pole hangs over the canal. It can be hard to see as I try to point Aleau towards it so Jeannie can grab it. I slow to a crawl as Jeannie turns the pole and triggers the lock. As with the remote control, a yellow light on the board at the lock lets us know the signal has been received. No yellow and we must track down someone to come fix the problem.

The task for me is to guide Aleau so the pole lines up perfectly with Jeannie’s hands.

Here’s what we like to see. The yellow light letting us know our signal has been received along with the green and red that indicate the lock is being prepared for us. In this shot, the lock doors are almost fully open. In a second, only the green will be lit and we can go in.

On the right in the shot above, there are bollards where could tie up if we had to wait for another boat coming out of the lock. Murphy’s Law says when there is a convenient mooring spot like this one, we don’t need it. Usually, when we do have to wait, both sides of the canal look like the left side – nowhere to moor. No way to even get close to the shore. And often, even more narrow – just when a commercial is coming out of the lock and we each have to squeeze past each other. Each day is an adventure.

Actually, each lock is an adventure. Each time we approach I ask myself, “Am I really going to be able to get Aleau in that tiny hole?” The lock is 5-metres wide. Aleau is 4.8-metres wide. She’s also 20-metres long. Her tall wheelhouse is great at catching any wind coming from the wrong direction. Even the slightest breeze will have Aleau’s stern deciding to go sideways instead of straight.

The one above was easy. (Easy being a relative word.) It’s not just a crosswind (although it often seems like a cross wind) that can create havoc. Sometimes there is a torrent of water flowing right across the entrance to the lock. Why would anyone design a lock like that? On one canal, they are all like that. It is a challenge.

Aleau has a stern-thruster. I should say ‘had.’ It died when we most needed it. It’s a hydraulically powered propeller, deep underwater, that sits sideways at the stern. When the bow is well into the lock and wind or a current wants to push Aleau sideways, I can use a joystick (to port or starboard) to straighten her out and maybe get Aleau into the lock without any scratches to our new paint job.

There is an alternative. Turn the wheel as far as it will go in the direction the stern is going and give a blast of throttle. It’s like turning into a skid in a car. Except there are just a few centimetres on either side and trying to get Aleau straight is a dance. As Jeannie will attest, I cannot dance.

We are booked into a shipyard to have the stern-thruster repaired. Because the thruster is underwater, Aleau has to be taken out of the water. An expensive part plus an expensive repair job. Be prepared to see far fewer restaurant pictures.