We left Péronne better informed about the so-called Great War – and the horrors that happened along the Somme.

Facing the dark tunnel now seemed inconsequential.

This time, we gambled – although we hedged our bets. We’re going to go through with the mast up so we can use our tunnel light. You can’t see it in the shot above as it is facing forward on the cross-member of the mast. What you can see is our radar reflector. It’s the tall column to the right of the orange light on the cross-member. It’s adjustable. It’s probably best if we lower it. By the way, the orange light is a horn light. It illuminates when we blow the horn. Vitally important in the dark.

In the shot above, we’ve lowered the radar reflector. We’re still worried about our mooring light at the top of the mast. The law says it must be on when tied up for the night in dark areas. Common sense says so, too. We will be moored in many dark spots before we make it back to Paris. We cannot afford to damage that lamp.

Oh, what a relief! Our tunnel light works! Perhaps even more important, the mooring light clears the roof of the tunnel. So does our weather station. The radar reflector, if we hadn’t lowered it, would not have survived.

The cabin roof that you see in the photo above is not the full width of Aleau. She actually extends another 51 centimetres (20 inches). On each side! But I can only see the cabin roof. Jeannie watching and guiding me is crucial.

Once we’re out, we’re happy. Not only because we made it through the tunnel but because the locks on the Canal du Nord are wider – although not by much. They are, however, very dirty. You can guess what our ropes look like by the end of the day.

Aside from how dirty locks can be, the photo above shows what no barge pilot wants to learn the hard way. When going downstream, the lock will be full of water. The barge passes through the doors and past that concrete sill. At least that’s what’s supposed to happen. When the lock is full, the sill is invisible. It’s covered with water. As the lock is emptied, the barge drops with the water. If any of it is over the sill – well, that’s something you don’t want to even imagine. On some locks, a white line is painted so bargees know exactly how far the sill extends. On many locks, it’s up to the crew. The longer the barge, the harder it is to make sure it is well past the sill.

On the bright side, the view from up high in some locks is spectacular.

Tunnels and locks aren’t the only things that require keeping a sharp eye out. Bridges can be very low. Failing to crouch down when passing under some of them could be fatal. Failing to lower the Bimini would be frightfully expensive. We destroyed an AIS antenna on one bridge. We came close to losing our radar reflector on this one. We have a friend who had his beautiful, wood mast chopped in two. Failing to lower a mast – even if (by luck) you safely make it underneath – is a sign of fatigue. Find somewhere to tie up and rest.

We arrive at the grain terminal in Noyon that barely had room for us a month ago and find it empty. In France, everything and everyone takes a full month off – either in July or August. Here, it was July. Luckily for us.

We woke up to find not all work had stopped. Spider webs littered the aft-deck.

The next day we arrived at our favourite spot in Compiegne. When we first started barging, we were the only ones to tie up here. This summer, on the two times we’ve been here, we were lucky to get the last spot.

The sun was shining brightly. It was so bright, we got to use our rarely needed sun shade that attaches to the rear of the Bimini.

One of the joys of barging is bumping into friends. We spent time with Marcel and Marina, owners of the beautiful barge Miro, when we were rafted together in Auxonne in 2019. (We hadn’t yet got the Aleau names plates to cover her old name, Gillian B.)

We spent time together again when we were both in Moret-sur-Loing in 2022. That’s Miro in the shot below. We’re nearby but out of the shot.

And we were delighted to see Miro moored in Compiegne as we approached two days ago.

They joined us for drinks on Aleau’s aft-deck – and the next night, they prepared a delicious dinner for us. I had cow tongue for the first time. I did not use a fork.

It seems a week doesn’t go by without us seeing fellow bargees who we’ve met over the years. It really is a small world.

It’s our fourth time in Compiegne. It’s still a joy to explore.

My birthday happened to fall during our stay in Compiegne. Jeannie tried to make reservations for dinner – but as you have read – not only do you need to make reservations in France, you need to do so early. The restaurant Jeannie wished to try was already fully booked for dinner. A table was available for lunch. I was more than happy with lunch.

We ate outside. That’s Jeannie going ahead to choose a table.

Once seated, what else but Champagne for me and the restaurant’s special cocktail for Jeannie?

It’s made of vodka infused with the juices of fresh peaches, apples, pears, and raspberries. She appears to like it.

That’s not the name of the restaurant over Jeannie’s shoulder. It’s a nearby wine bar.

In fact, there are many places to eat along this pedestrian-only street.

The name of where we’re eating is clearly marked above the door.

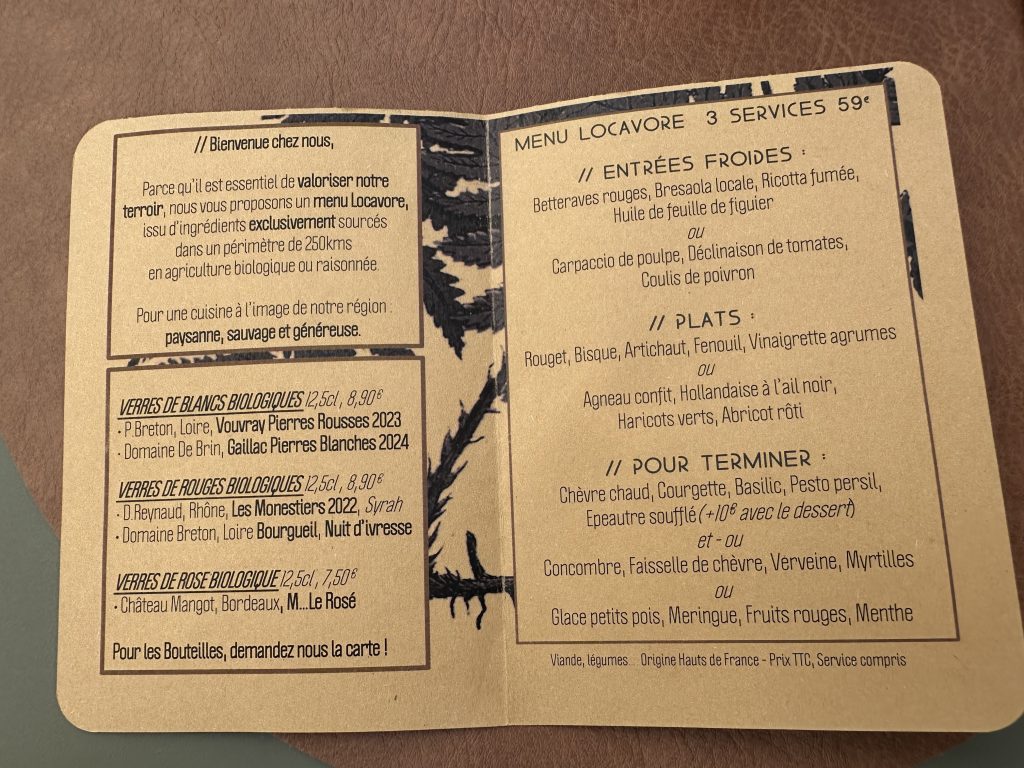

As with the best restaurants, the menu is small – two entrées, two plats, two desserts – plus a cheese plate.

We began with a carrot amuse-bouche.

For an entrée, we both chose smoked ricotta crowned with beets.

We both chose the same plat – fork-tender lamb confit with a black, garlic foam along with roasted apricot and green beans.

Dessert for me was a baby-pea ice cream (Yes, you heard right.) with meringue and fresh fruits.

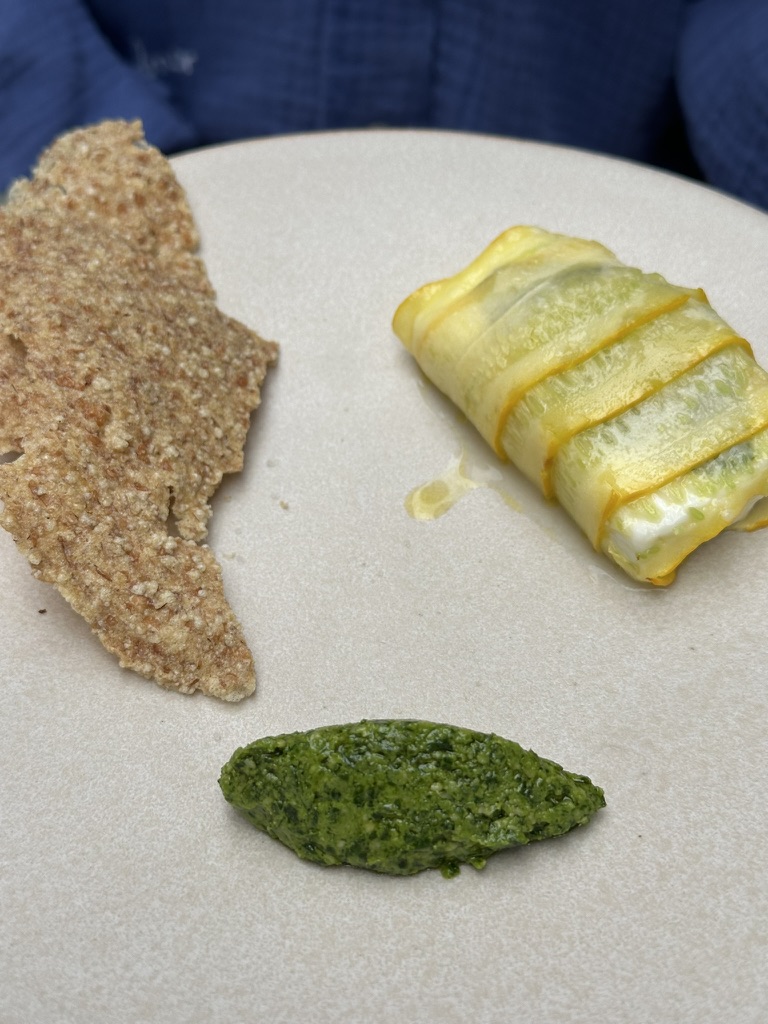

Jeannie ended the meal with warm goat cheese with fresh basil leaves wrapped in yellow zucchini – served with parsley pesto along with a spelt wafer.

It was a wonderful birthday lunch.