It has been called The Great War and The War to End All Wars. It was neither.

In July of 2025, we traveled the Somme from Péronne to its end at the English Channel. It was a joy. In July of 1916, it was not. It was a site of horror and carnage. On one day alone, July 1, 1916, 20,000 British soldiers were killed.

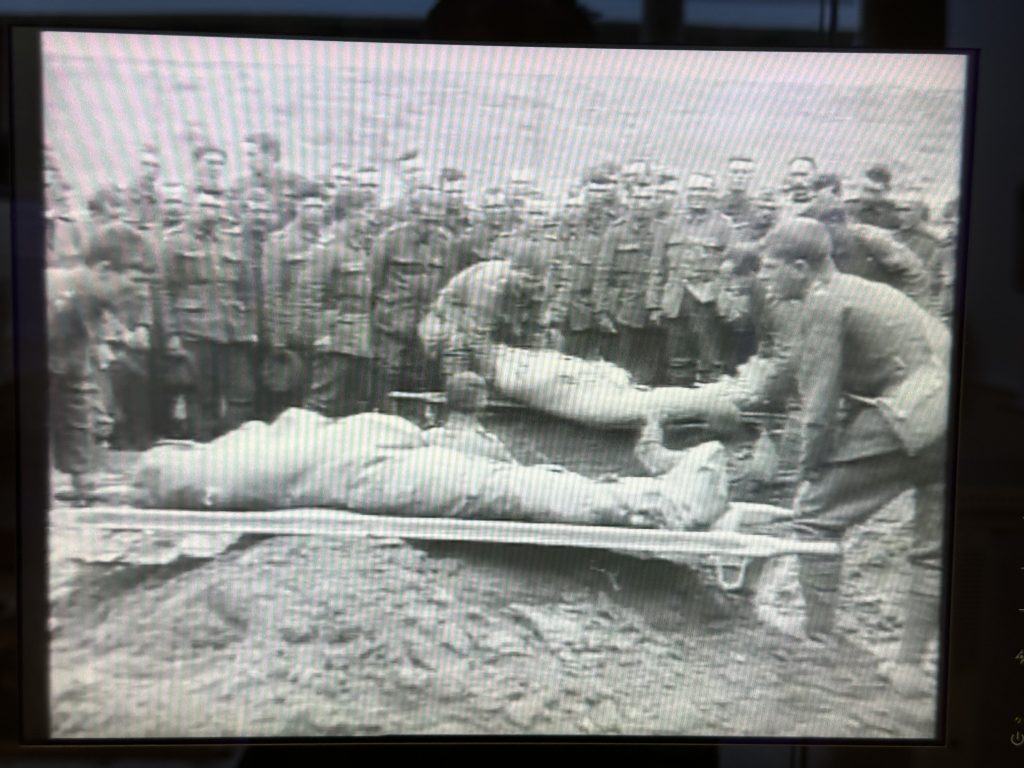

The Battle of the Somme is one of the deadliest battles in human history. It is impossible to recreate the suffering of what happened along this narrow, twisty river. No words, photos, nor films can come close. The “Historial de la Grande Guerre” Museum in Péronne uses all of those to give viewers a glimpse of that battle. More than 70,000 documents and artifacts help visitors come away better informed.

Many countries came to the aid of Britain. They all lost thousands of lives. Their dead are buried in dedicated cemeteries along the Somme. Photographs of them line the entrance to the museum.

In the British cemetery, half of those buried were never identified.

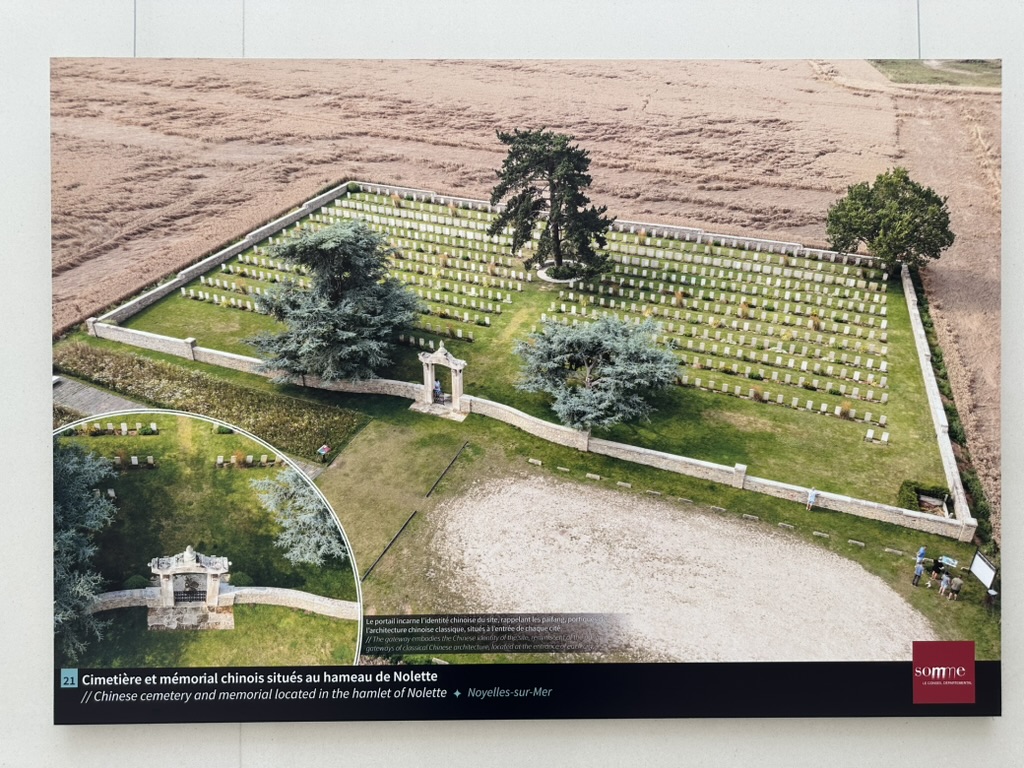

Of course, France has a cemetery – so do Australia, China, and South Africa. All for lives lost along the Somme.

Newfoundland has its own cemetery as it was not yet part of Canada. More than 100 years later, its cemetery is still pockmarked from the artillery that rained down throughout the area.

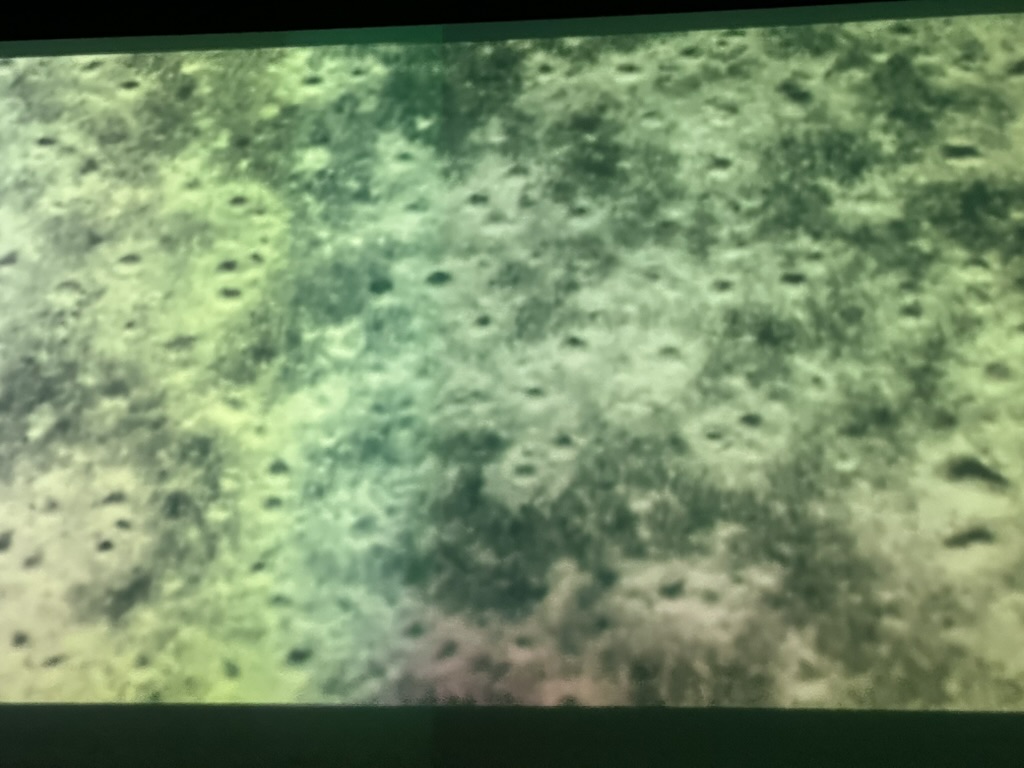

Just what the land looked like at the time is shown in this shot taken from a reconnaissance biplane.

The First World War marked the beginning of aircraft playing a pivotal role in battle.

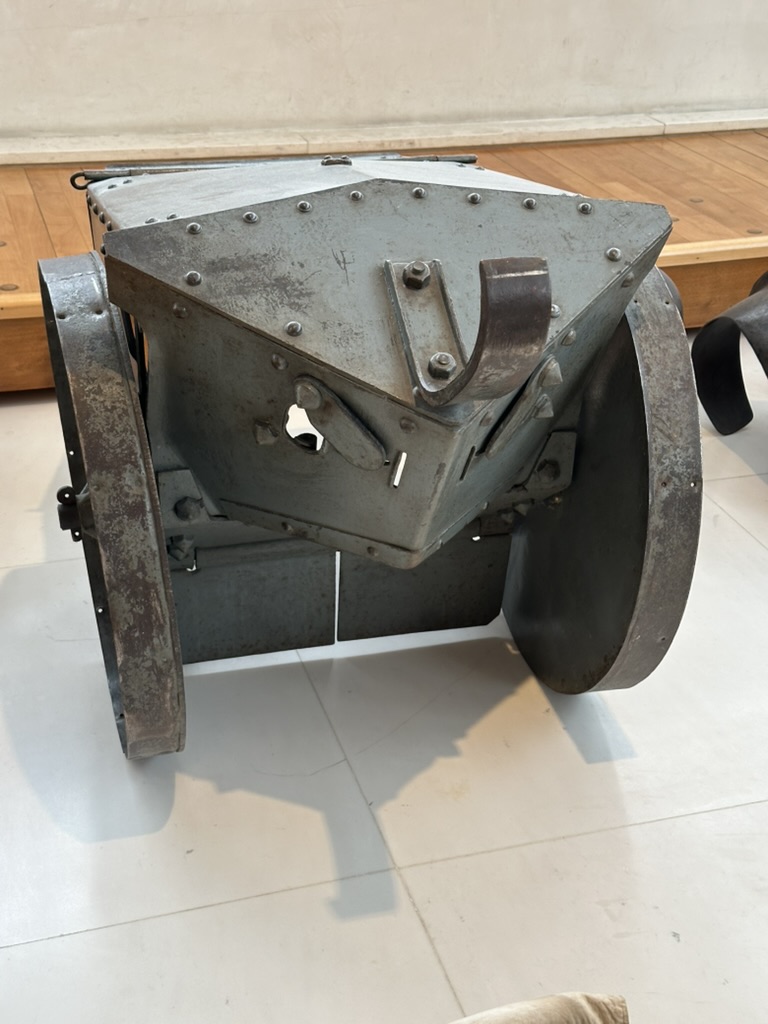

Motorized tanks also saw their first appearance. But some soldiers had to make do with crawling on their hands and knees pushing their protection in front of them.

No protection was strong enough when facing the massive artillery used by both sides.

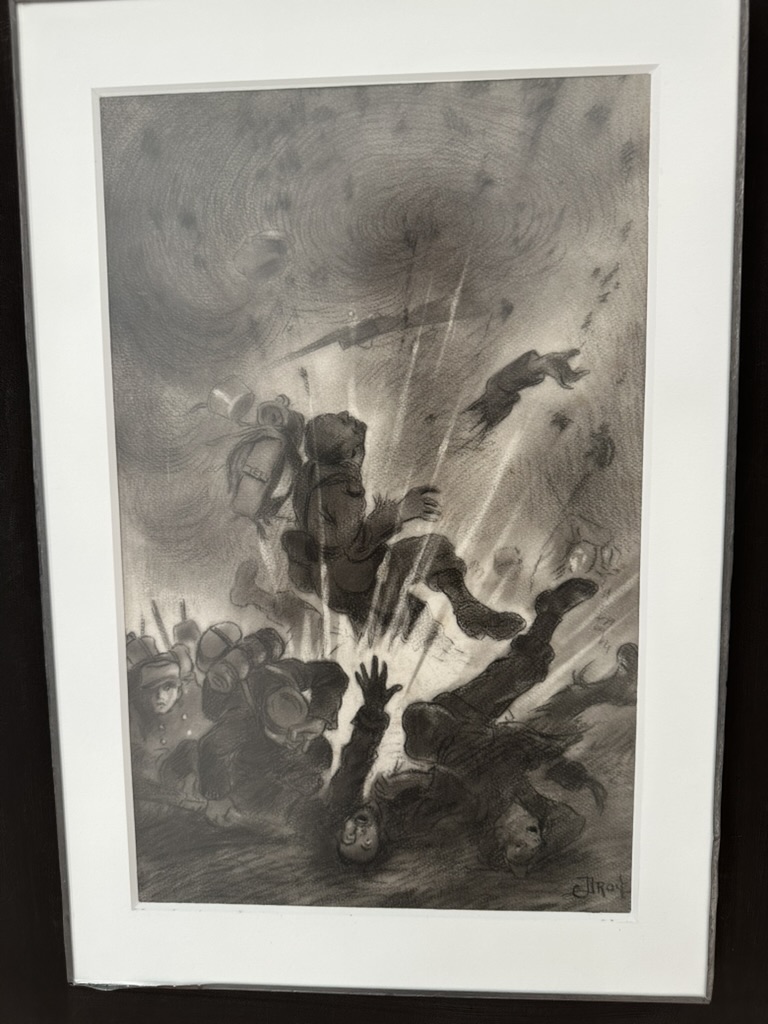

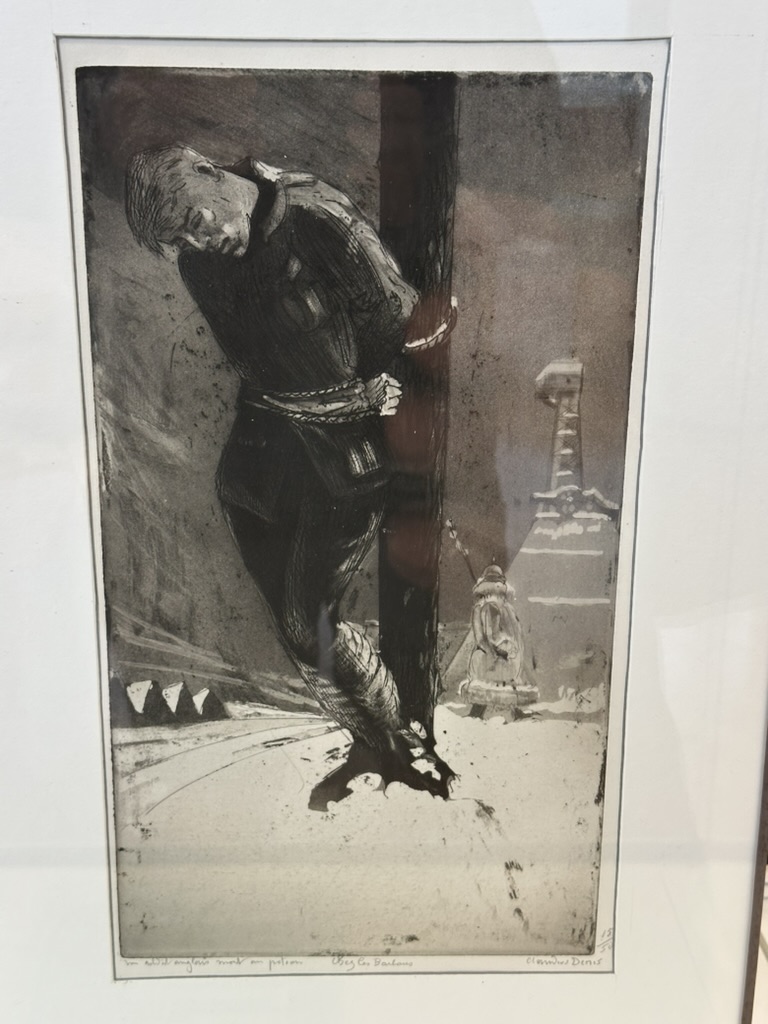

As photographers were documenting death along the Somme, so were artists.

This one depicted torture by German soldiers.

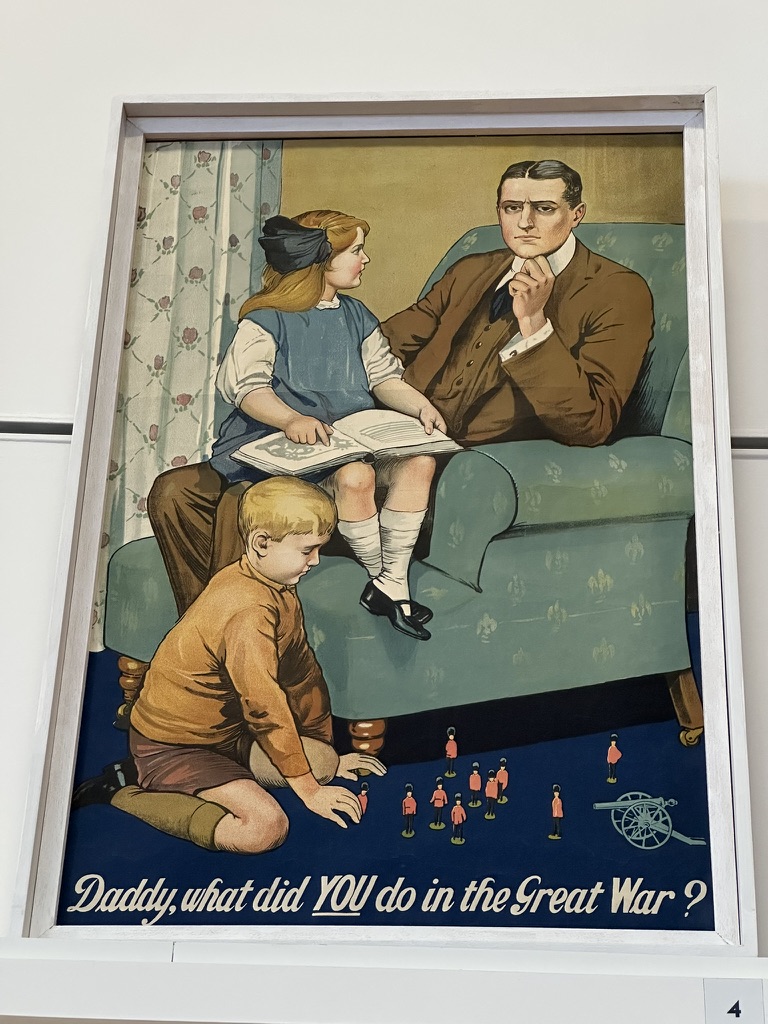

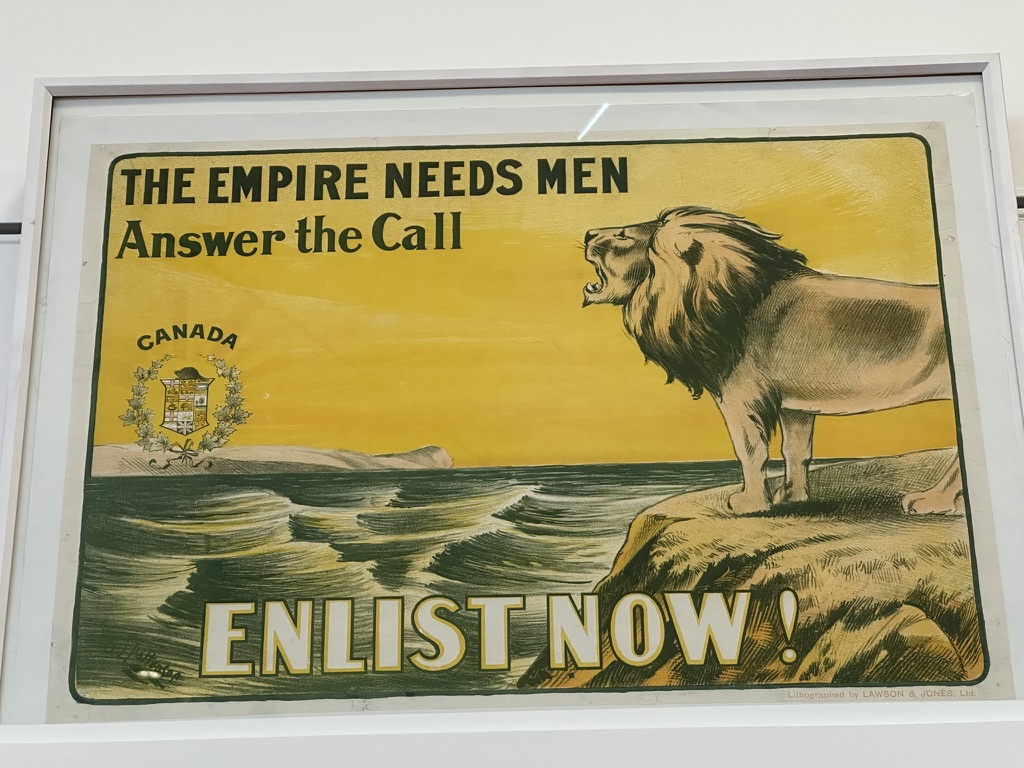

Art was also used to recruit.

Canada, too, had a recruitment poster.

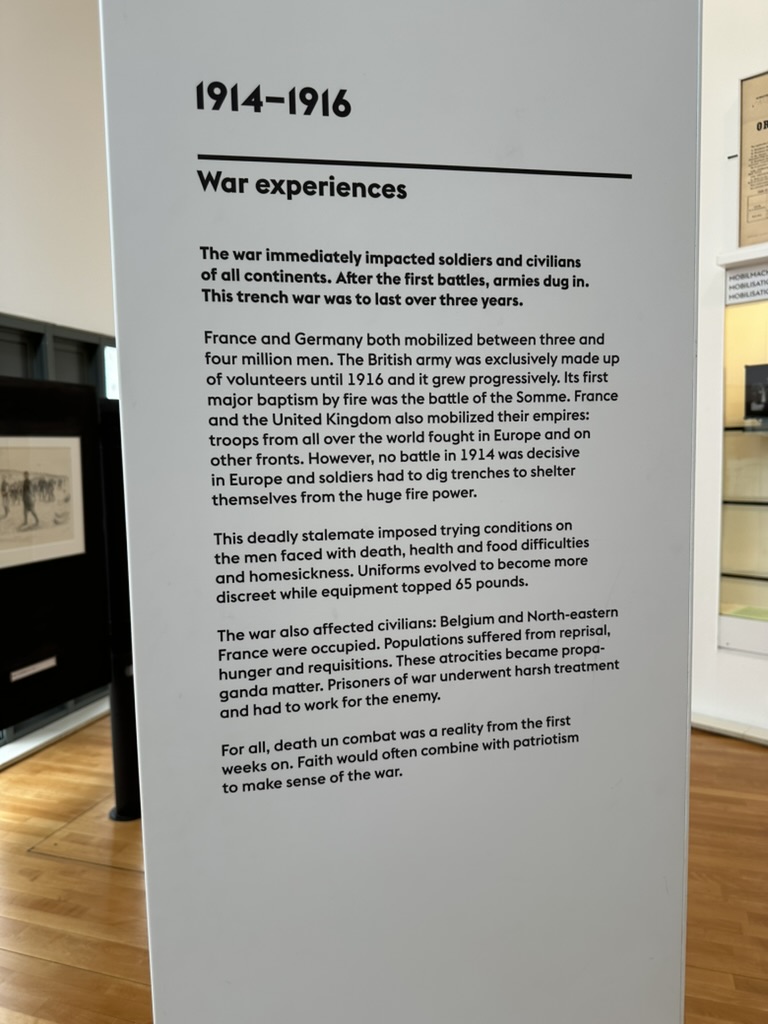

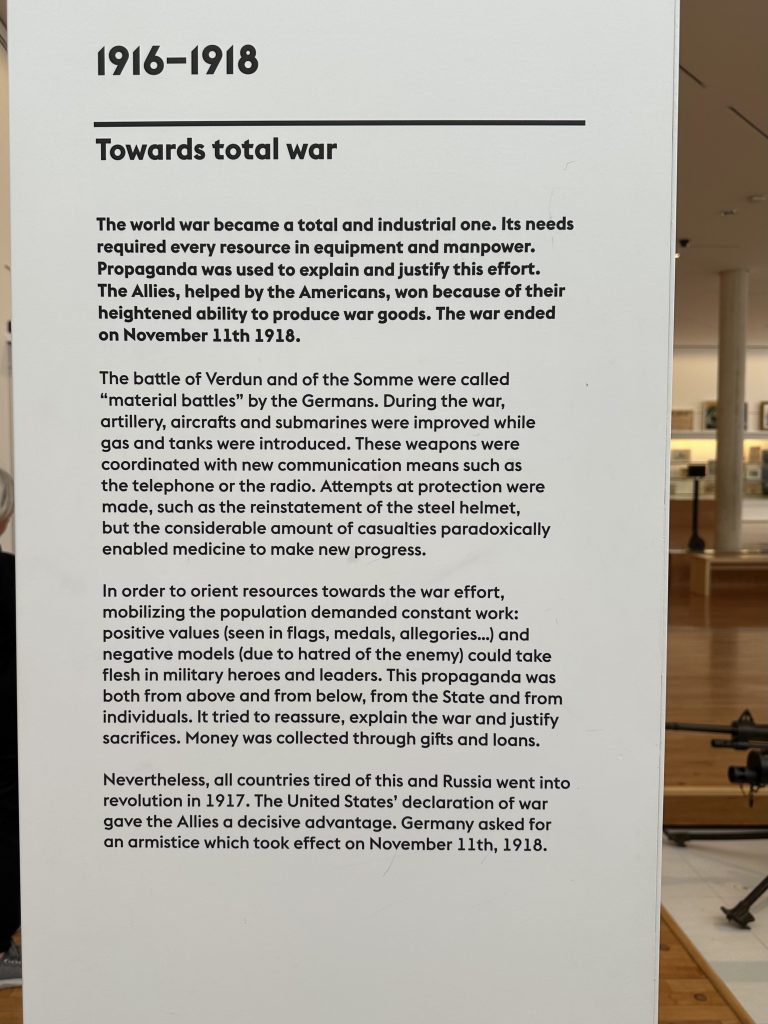

Throughout the museum, boards display in chronological order the course of the battle.

The museum has displays of what was used to take lives.

And what was used to try to save them.

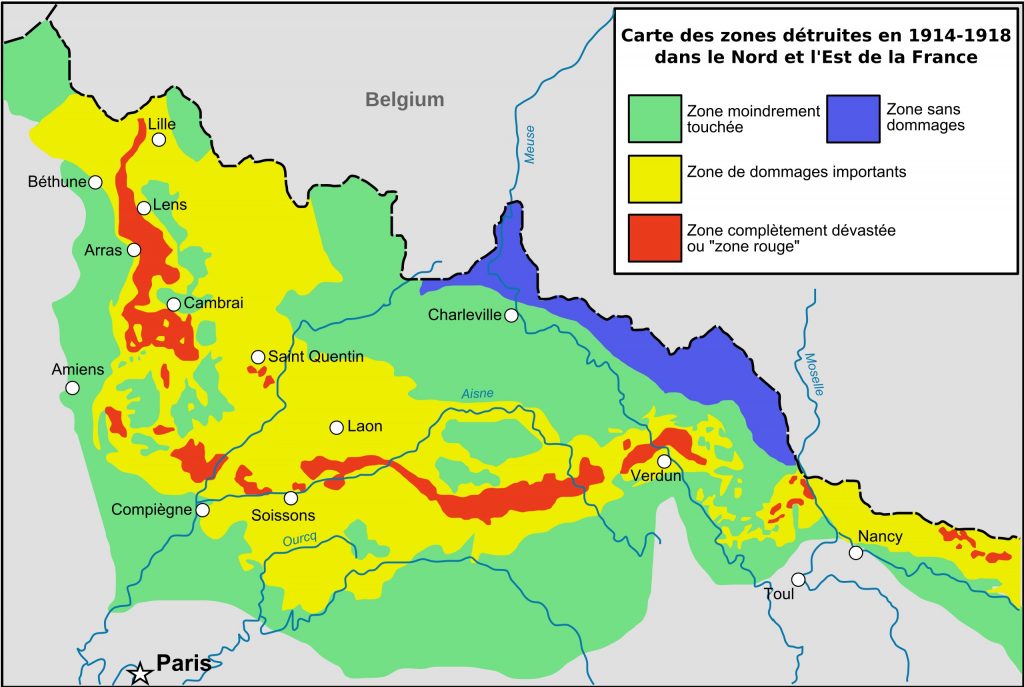

While the museum looks back on what happened more than 100 years ago, the war remains a danger today. Parts of France have been declared ‘Red Zones.” No one is allowed in.

Much of the 1,200 square kilometres originally classified as red has been made safe. Experts say it will take up to 700 years before the red zone can be entirely eliminated. Those areas remain saturated with millions of unexploded shells, both explosive and gas. It is estimated that there are 300 unexploded devices per hectare (120 per acre) in the top 15 cm (6 inches) of soil in the worst areas. Some towns and villages were never allowed to be rebuilt.

Given how France has suffered, it is no surprise that children learn about the First World War at an early age. The bookstore in the museum is stocked with a number of titles just for them.

For children who lived in that era, the war was a part of life. A mini machine-gun took the place of a toy car.

The “Historial de la Grande Guerre” is just one of the many spots in France where the First World War is not forgotten. In Dormans, on the Marne, there is a majestic monument honouring those who died.

We visited it in 2023. There are more photos of it in Chapter 204.