When we left Compiegine, we were on new waterways, new to us at least. We were eager to see what they would bring. Our first discovery? It appeared nobody else was on them. Just after Compiegne, we turned right (east and upstream) off the Oise river and onto the Canal Latéral à l’Oise. It took us almost seven hours and four locks to get to Chauny. And we didn’t see a soul – at least not on the water. We tied up for the night – no water or electricity – but we knew our batteries would get us through the night and the engine would recharge them once we resumed cruising in the morning.

Chauny has a few nice buildings. The Mairie was, as in almost every town, the most impressive.

The train station was a close second.

Our time in town was no different from our time on the water. The streets of Chauny were deserted. There wasn’t even a restaurant that was open.

The next morning, we got an early start. Only to have to wait for the world’s slowest lift-bridge to raise.

With hardly any room on either side, Jeannie is at the bow to help me through.

As we passed, I could look back and see a line of cars on either side – perhaps grateful that we were the only boat on the canal that day.

We had to wait even longer at this swing-bridge for the light to turn green.

It wasn’t long before the rain came down and it was time to retreat and steer from the wheelhouse. I don’t think there has been a day this year when it has not rained.

We are now on a new waterway.

The canal is needed along this stretch as the Sambre, while pretty to look at, is not deep enough for boats.

Mézières to Vandencourt had us feeling exhausted. 21 kilometres and 11 locks. Once again, a “wild mooring.” No services – but scenic.

Today is a holiday in France. Everything is closed. Except the local bar.

They were kind enough to put down their drinks for a second and grab a shot of the two of us.

Another day. Another lift bridge. Another wait for a green light.

And another tight squeeze.

One more bend (and a lock) and we’ll be done for the day.

Or so we thought. We spent an hour trying to figure out how to moor. Aleau is too long to moor in the fingers at most marinas. Fortunately, the last two fingers are usually flush on the outside (called a “hammerhead”) giving us more than enough room to tie up. Not so here. In a twist to the fingers we’re used to, here, the top of the T is not flush – making it unavailable to us. Did they do that on purpose?

I tried everything I could. Finally, after an hour, I decided to do something that is probably frowned upon. I would moor against the end of the fingers. I’d take up five mooring spots – but since there were no other boats, I didn’t think it would be a problem.

Timing is everything. It wasn’t long before two boats appeared. They were coming from the other direction which is why, up until now, we had had the canals to ourselves. I was glad I had been able to tie up before they arrived.

It turned out to be a lovely spot to spend the night.

The next morning, we were back on a very verdant canal.

And back tying up traffic.

We stopped for lunch in Landrecies. We ordered Champagne. It came with potato chips.

While in Landrecies, nine days after leaving Compiegne, we saw our first boat coming in the opposite direction. Bargees from Australia. We meet more Australians than any other nationality.

We found a mooring in Hautmont. We were too big to fit in the marina – but with a long cord and hose we were finally able to get electricity and water.

We also made a friend.

We had lunch at a buffet restaurant. There must be others – but this was the first buffet restaurant I have seen in France. It was typically French. While you could eat all you wanted, coffee was not included in the price. Neither were refills. If you wanted beer or wine, well of course, help yourself – to as much of either as you would like. An extra charge for coffee – but all the wine or beer you can drink.

Beer on tap on the left. Wine – white, rosé, and red on the right. Help yourself. Coffee? No, there’s an extra charge for that.

On May 9th, 17 days after leaving Paris, we crossed the border into Belgium. If we had been on foot, on a bike, in a car – or gone by train or plane, there would have been no formalities. But when you cross the border between EU countries in a boat, there’s a thorough inspection of all your paperwork – especially the boat’s. Licenses for it and the VHF radio, proof of insurance – as well as my license to operate both Aleau and her radios. After filling in a lengthy form, we were allowed into Belgium.

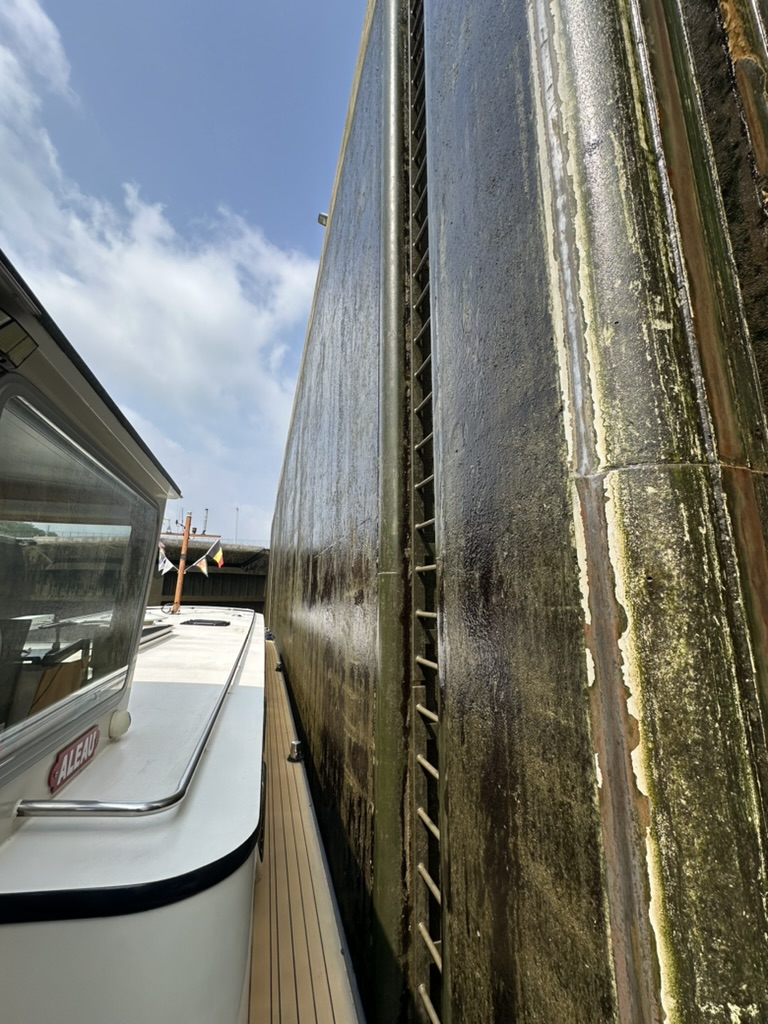

Our first lock in Belgium was interesting. There was a bridge across it. We thought they’d raise it and we’d proceed to the end of the lock. Nope. We had to come to a stop at what appeared to me, steering from the stern, to be just centimetres from the bridge.

Jeannie was there to yell, STOP!.

We began dropping – but not enough to squeeze under the bridge.

Bells rang, gates to stop cars lowered, and then the bridge went up.

We found a mooring for the night in Fontaine-Valmont. Sitting inside, we suddenly heard the most god-awful racket. We rushed to the wheelhouse to investigate. It was an invasion, a very loud invasion. They had seen a new boat arrive and came to beg for food.

At night, they bedded down just across from us. Probably dreaming about breakfast supplied by Aleau.

Yup, with dawn’s first light, they were there.

One of the many joys of barging in Europe… It seems no matter where we stop – whether for the night – or here in Thuin, Belgium while waiting over lunch for the lock to open, the views are almost always magnificent.

We have taken down the Canadian flag we have proudly flown since beginning our barging life and replaced it with a Dutch flag – but just temporarily. Aleau is registered in the Netherlands. Which means by law, we must fly a Dutch flag at the stern. It might raise eyebrows as we crossed borders to have a Canadian flag. Once we have finished crossing borders, the Canadian flag will be back. (But don’t tell anyone.)

Along this stretch of the Sambre river, lock-keepers must open and close the lock gates and the sluices by hand. But since we seem to be the only boat out today, they won’t get much of a workout.

More sights as we cruise along the Sambre.

More locks – and more bridges to pass under.

What’s this – another boat? We haven’t seen one of those in a long time. We actually have to pull over and wait for it to leave the lock – being careful to not get too close to the shallow shore.

We passed under bridges built with new technology and with old.

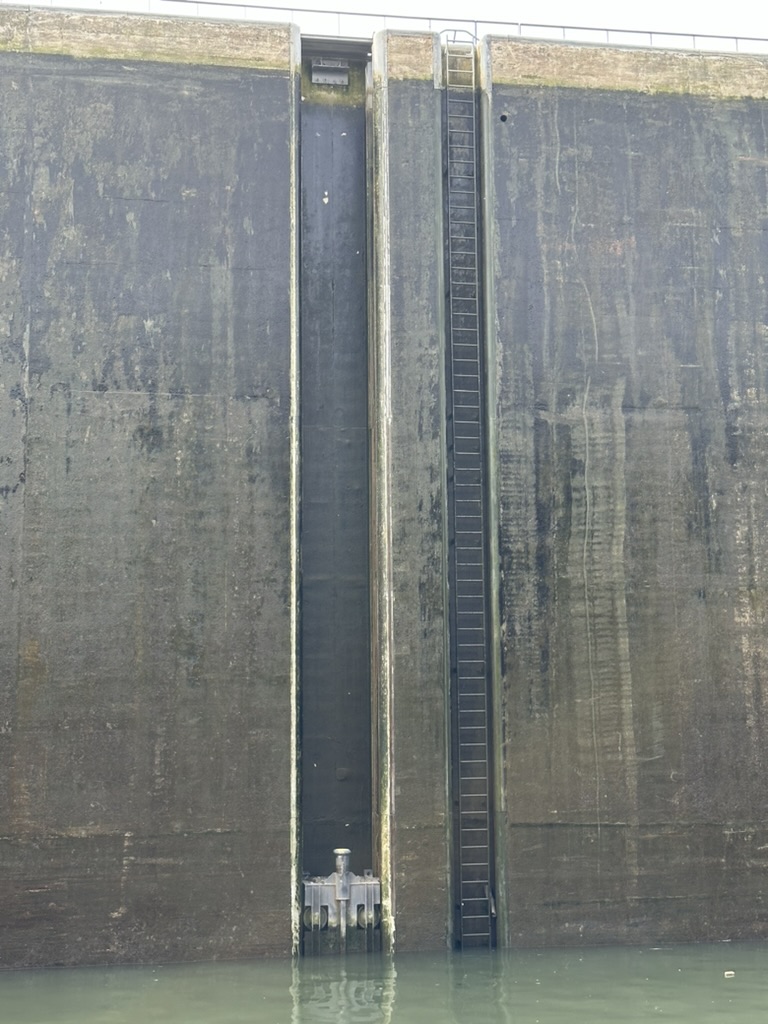

As we approached Charleroi, Belgium, conditions changed. Gone were the tiny, hand-operated locks we could pass through in 10 minutes. It was now taking one-and-a-half hours to pass through the large, automated locks. Progress?

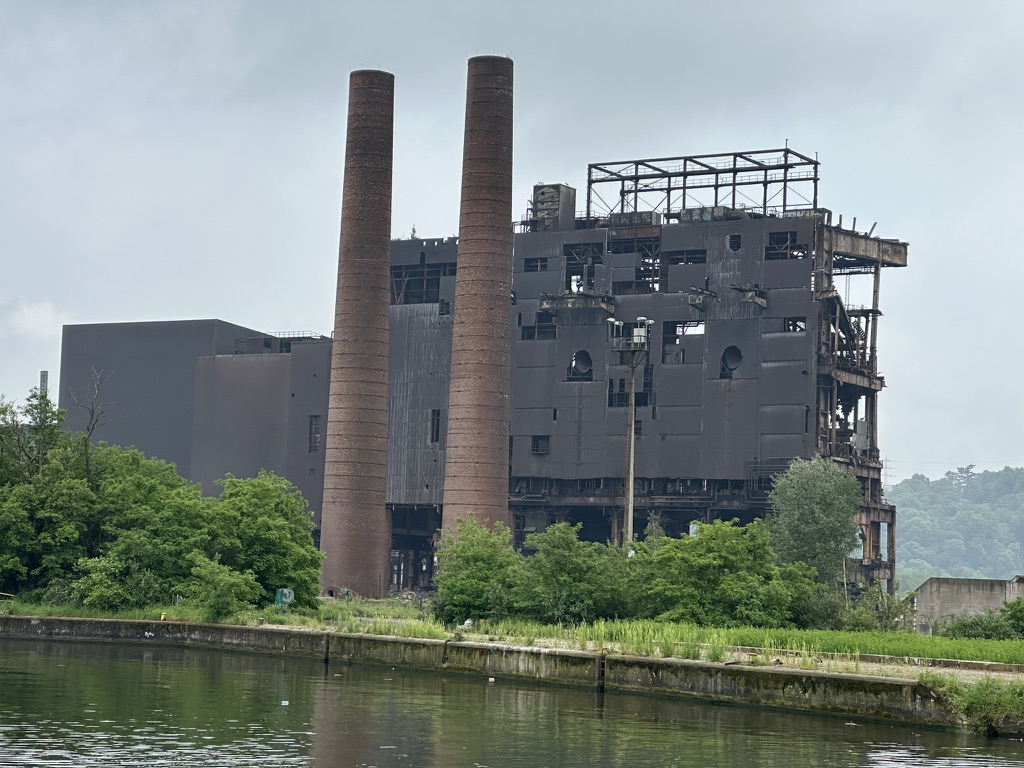

From dystopia to utopia. Barging through Charleroi was seeing two different worlds in quick succession.

All of a sudden, a completely different view of Charleroi. Quite attractive with a mixture of old and new.

There was nowhere to moor in Charleroi so we continued on to Tamines. And continued past Tamines when we didn’t see anything there. As mooring against the bank was impossible, we turned around and had another look at Tamines. Success. Sort of.

We moored against a high wall. A bit of agility (and nerve) was required to get off Aleau.

We may have left Charleroi – but there were constant reminders it was not far away – loads of scrap metal going to the recycling plants we had passed. The captains of these 100-metre plus barges were all considerate – slowing as they passed to reduce the wash that would have Aleau rocking.

Our next stop was the highlight of the trip so far – Namur. It marked the end of the Sambre and the last few metres on it were a joy.

Namur is best known for its massive Citadel – overlooking and years ago, protecting the city. The original was built in 937 with construction of the present Citadel begun 1631. Aleau is the second boat from the left in the photo of the Citadel below. We’re now on the Meuse as the Sambre ended a few hundred metres downstream from where we are moored.

Immediately above us is Namur’s casino. We didn’t go in.

The casino may not have tempted us – but this sign did.

Until we read the fine print. Free WiFi. Cold Beer. But it did get us to cross the street.

Namur is a lovely town to explore.

There was a line for ice-cream. Was it really imported from Australia?

Somebody in Namur drank a lot wine in order to make this ship – constructed almost entirely from corks.

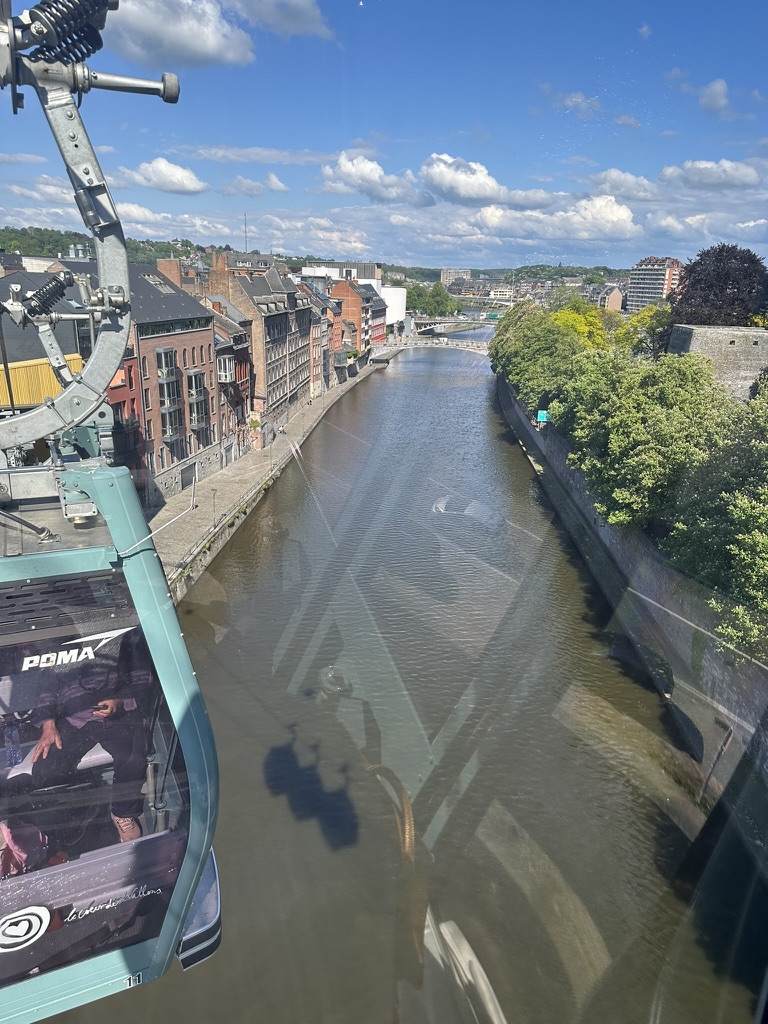

While the Citadel was built 400 years ago, we chose a modern way to get to the top. By gondola.

We could look down on the final few hundred metres of the Sambre…

And on our next river, the Meuse.

At the top, we found what appeared to be an old amphitheatre.

It’s now used as a parking lot.

We wished we had a car with us. Not to use the parking lot – but to take advantage of all the hairpin turns winding down from the Citadel.

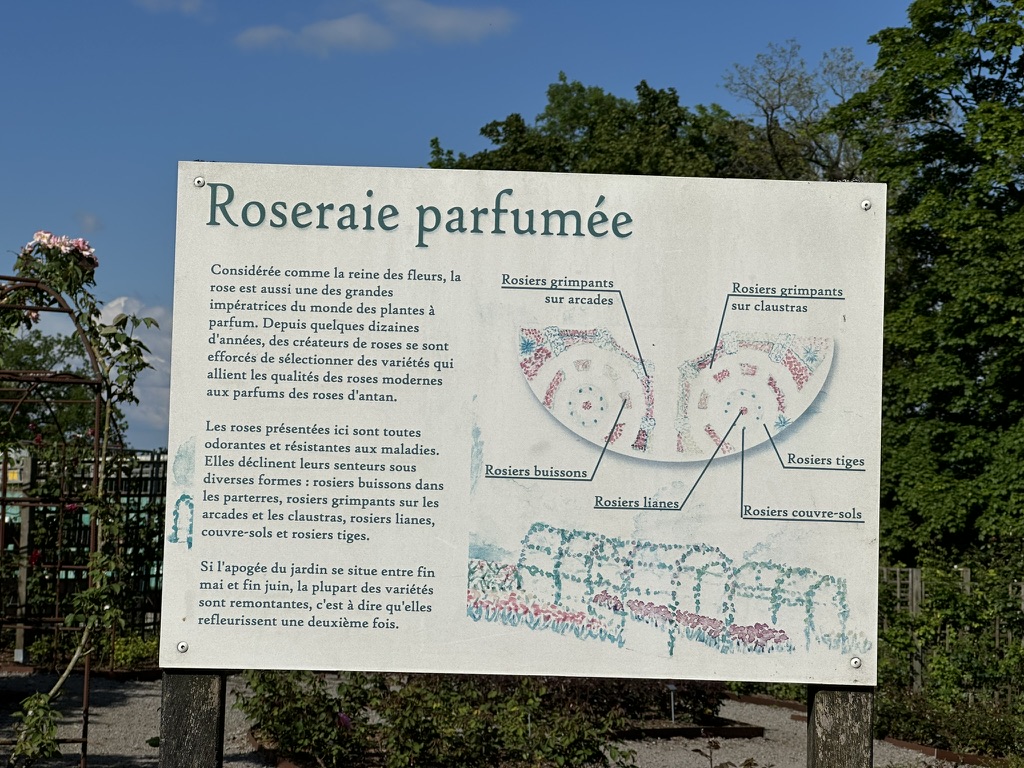

At the summit sits Château de Namur, a hotel and restaurant surrounded by fascinating gardens.

There’s a rose garden where visitors are encouraged to take in the scent from the various varieties.

Nearby, a garden where you may not want to take in a big whiff.

Then, a garden where you wouldn’t even want to touch the plants.

Don’t touch!

I found this section more palatable.

In addition to the various specialized gardens, there were plants that were there just to enjoy.

We took the gondola back down. (Those hairpin turns wouldn’t be as much fun on foot.) We got more looks at the Citadel. Unfortunately, we ran out of time and weren’t able to explore the interior. Next time.

A sight we weren’t expecting as we passed over the Sambre… A barge carrying coal heading downstream and one that had just gone by in the other direction. I’m glad they weren’t there when we passed by. It would have been a tight squeeze on that bend.

When we got back to Aleau, we found friends who were moored in front of us in Paris were now moored in front of us in Namur. It’s a small world. Wayne and Liz, on Anahita, are from Australia. Isn’t everybody we meet on the waterways from Australia? To celebrate the reunion, some Crémant. Of course.

After an enjoyable evening onboard Anahita, it was time to cast off. Our next port was Huy – on the Meuse. The town looked inviting. The marinas in it did not. We were informed by signs that we were too big. Disappointed, we pressed on. We did find a spot we could squeeze into. Across from a nuclear power-plant. Free electricity – if our batteries could handle 200,000 volts. And if we didn’t mind glowing in the dark.

A red light. The story of our life on the Meuse.

Red and green – the lock is being made ready for us. Good news.

Until we saw the flotilla of large commercials exiting the lock.

Locks that we get through in ten minutes were a thing of the past. It was now taking us an hour-and-a-half to get through each one. Finally, the last barge leaves and we can go in.

As we slowly descended in the lock, some good news. To speed things up, a second lock is under construction. It’s massive – but won’t be finished until next year.

The one being built alongside will make the one we’re in now look tiny.

The tedium of taking 90 minutes to pass through a lock was relieved by the sights in between locks.

In Liège, we passed by two marinas that said we were too big – and then one that allowed us in. The skyline included a phallic-shaped building that seemed similar to London’s Gherkin.

At night, Liège’s bridges brought some colour to what had been a very grey day.

The bridge behind us was constantly changing colour.

We enjoyed Liège. Since it’s in Belgium, Belgian chocolate was featured.

As were Belgian burgers – although I’m not sure what makes them different from any other burgers.

Belgium is a country divided. Wallonia is entirely French. Flanders is entirely Flemish.

Since Liège is in Wallonia, it was no surprise that parts of it reminded us of Paris – from bridges to covered passageways.

On the outskirts, sights that reminded us more of Charleroi.

We have now left Belgium and crossed into the Netherlands. Once again, a red light and a long wait. (Eagle-eye readers will notice we are still flying the Belgian courtesy flag. I will take it down at the earliest opportunity.)

We learned – the hard way – that locks in the Netherlands function differently than what we’re used to. It came very close to being a disaster.

To make life easier, there are floating bollards. We are used to them. When descending in the lock, we loop a rope around the floating bollard and tie it to the bollards on Aleau. It works great. Aleau and the floating bollard descend together and we untie at the bottom.

We didn’t know that in the Netherlands, the floating bollard doesn’t begin to descend until the boat has already dropped a metre. Jeannie and I freaked. Aleau was dropping. The bollard wasn’t. Aleau started hanging from the floating bollard. Jeannie grabbed her knife (always in her pocket when descending). She was about to cut us loose from the bollard when it suddenly dropped. Safe! But the drama wasn’t over. When we reached the bottom, the floating bollard remained one metre above us – putting so much tension on the rope, we couldn’t loosen it. Once again, the knife came out. This time, Jeannie had no choice but to cut us free – slicing through one of our expensive ropes. Lesson learned. For whatever reason, the Netherlands has decided to have peculiar (and potentially dangerous to those who don’t know how they work) floating bollards. Maybe, sometime, someone will be able to explain to me why they have chosen to do that. Maybe it’s easier for the large commercials that sit higher in the water – but the same size barges travel up and down the Seine with the more conventional type of floating bollard and seem to do so without any problem. We were not impressed.

Surviving the lock with the only damage being a cut rope, we arrived at Maastricht, our last stop before arriving at the shipyard in Maasbracht. The Maastricht marina has its own lock – smaller than the massive one we passed through earlier – and without floating bollards to cause us grief.

We got to Maastricht just in time to watch the superb seamanship (seawomanship, seapersonship?) of the captain of a tourboat as she manoeuvred through the tight confines of the marina.

Because there is so little room under some bridges, wheelhouses are often made so they can be dropped when necessary. Here the wheelhouse is in its normal, raised position – although its placement at the bow and not at the stern is unusual. The captain is focusing all her attention on the tight turn she must make – avoiding the fingers (and moored boats) directly in front of her.

Navigating was just as difficult (if not more so) a few seconds earlier. The wheelhouse was lowered so the boat could pass under the bridge. The captain is nowhere to be seen. The head of her first-mate is barely visible, his head sticking up at the edge of wheelhouse.

Once past the bridge, he’s able to stand and relay instructions to the captain – still hidden the the lowered wheelhouse.

Meanwhile, guests enjoy their meal – oblivious to the challenges happening above them.

Finally, the wheelhouse is back up – but there is still the stern to worry about.

Speaking of sterns, that’s Aleau’s stern at the bottom left in the photo above. The captain of Jekervallei not only has to avoid the fingers and boats in front of her, but us on her port side, and the rest of the bridge at her stern.

Once again, we were too big for the fingers.

While we were by ourselves, ostracized to the other side of the marina, the view at night more than made up for it.

We loved Maastricht. And it seems we weren’t the only ones. Maastricht’s population is 125,000. I think every one of them was out enjoying the city while we were there. Plus a few from Belgium – five kilometres away. And a few from Germany – less than 30 kilometres away.

It was impossible to find a sidewalk café or restaurant that wasn’t packed.

Once again, if we chose to, we could have eaten within metres of Aleau. (We chose not to. We decided to go where all the crowds were.)

One thing I wasn’t expecting to see in Maastricht (or anywhere else in Europe for that matter), a North American school bus. In Europe, children ride to school in luxury.

So I did a double-take when I saw this coming at me in Maastricht.

And then I read the sign on the side.

Not the most comfortable way to see the city. But if you’ve never ridden one…

When we got back to the marina, we were pleased to see Anahita, our Australian friends Wayne and Liz – first from Paris, and then from Namur – moored across from us. Our third time on the water together – but not the last.

The final day. Another busy waterway. Another massive lock.

It took five hours to travel the 23 kilometres from Maastricht to Maasbracht. We had arrived! We were now in Tinnemans Shipyard. Much work needs to be done. We have no idea how long we’ll be here. But we do have some pretty big company. Across from us, large commercials – in the dry-dock and out of the water as work is done. Next to us, more big commercials waiting for work to be done. It is going to be an interesting experience.

The yard is called Tinnemans Floating Solutions. In the chapters to come, a diary of the work being done and just what the floating solution is.